Montreal Cycling History

The 1899 International Cycling Association World Championship in Montreal

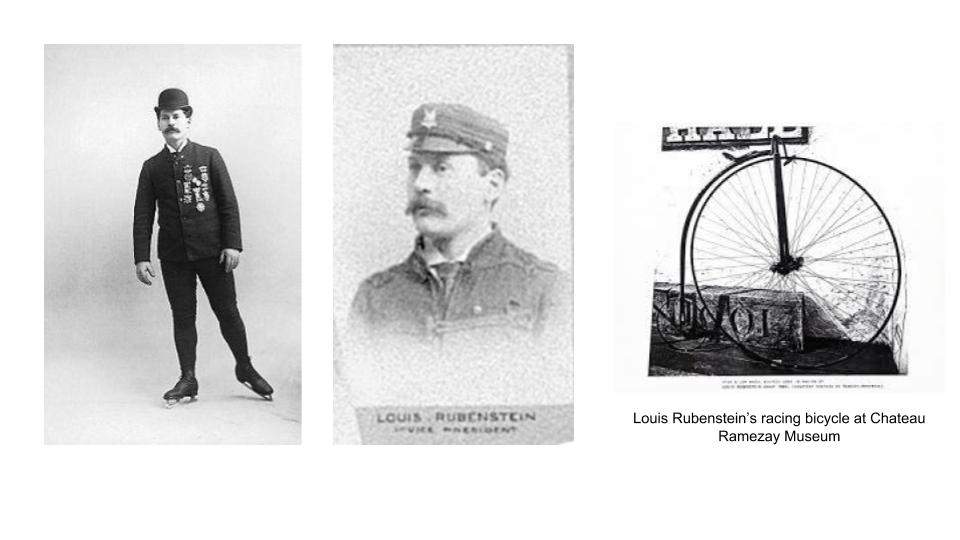

The Victoria Skating rink was also the home rink of another important member of the Montreal Bicycle Club, Louis Rubenstein. His parents were Polish Jews who had immigrated to Canada in the 1850’s. He took up figure skating (or fancy skating as it was then called) as a child, inspired by a show given by American Jackson Haines, the father of modern figure skating. Louis saw him perform in Montreal when he was just 3 years old. As a teenager Louis went to Vienna to train under Jackson, and then went on to be the US champion fancy skater in 1888 & 89. With a letter of introduction from Canadian Governor General Lord Stanley he travelled to St Petersburg, Russia for the figure skating world championship in 1890. St Petersburg at that time was a city “beyond the Pale” and it was forbidden for Jews to travel there. However, with a special request from the British embassy in St Petersburg he was permitted to compete, and became the world champion. He retired from fancy skating shortly thereafter and after the 1894 CWA meet in Montreal he became president of the Canadian Wheelmens Association, a post he held for 18 years.

In 1897 Glasgow, Scotland held the cycling world championship for both professional and amateur categories. Louis Rubenstein had the Canadian Wheelmens Association send a delegation to Glasgow in a to bid to hold the following year’s ICA World Championship in Canada. After the first World Championship in Chicago, (concurrent with the World's Columbian Exposition which featured the first Ferris Wheel) all others had been held in Europe. The Canadians lost the bid to Austria, but Sturmey agreed that if Canada sent a cycling team to compete in Vienna in 1898, (to be held at Prater Park beside the newly built Vienna Giant Ferris Wheel) the 99 world championship would be held in this country. Louis Rubenstein then took on the job of selecting a team, and choosing a venue between Toronto and Montreal, cities that both wanted the event.

In 1897 Glasgow, Scotland held the cycling world championship for both professional and amateur categories. Louis Rubenstein had the Canadian Wheelmens Association send a delegation to Glasgow in a to bid to hold the following year’s ICA World Championship in Canada. After the first World Championship in Chicago, (concurrent with the World's Columbian Exposition which featured the first Ferris Wheel) all others had been held in Europe. The Canadians lost the bid to Austria, but Sturmey agreed that if Canada sent a cycling team to compete in Vienna in 1898, (to be held at Prater Park beside the newly built Vienna Giant Ferris Wheel) the 99 world championship would be held in this country. Louis Rubenstein then took on the job of selecting a team, and choosing a venue between Toronto and Montreal, cities that both wanted the event.

Unfortunately, the cycling world’s organizations which had boomed in the early part of the 1890s’ began to unravel in the later half of that decade.

In the United States disagreements arose between racing promoters and the overall LAW over how professional racing should be handled. Racing interests founded a rival National Cycling Association in 1898. Both organizations had a racing circuit and professional racers had to choose which circuit to join. Major Taylor, chose the LAW circuit despite the fact he was barred, due to his colour, from actual membership, within that organization.

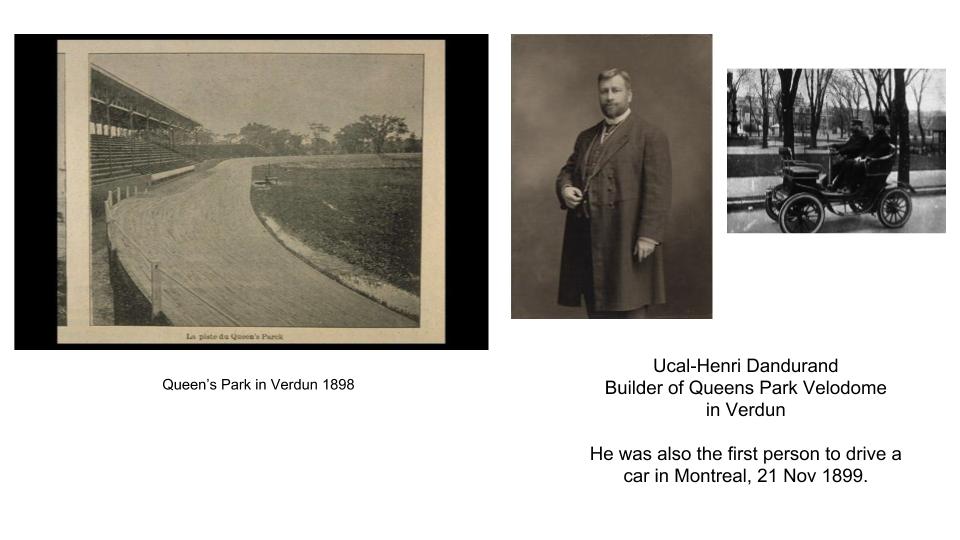

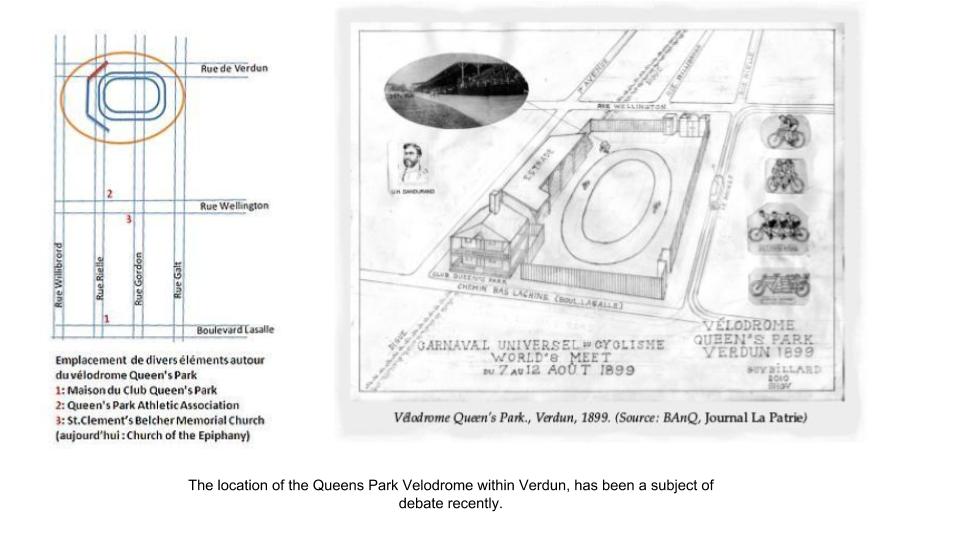

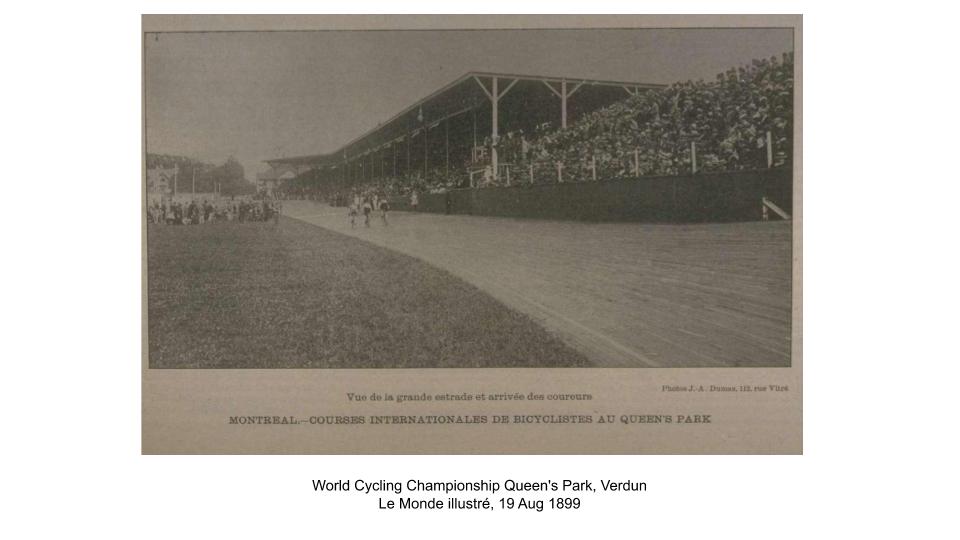

In Canada, Montreal’s case for the world championship was strengthened when a new outdoor wood Velodrome that could hold approx 12,000 spectators was constructed in Verdun by Ucal Henri Dandurand. Interestingly, Dandurand later became the first man in Montreal to own an automobile, something for which he is today best known for.

In the United States disagreements arose between racing promoters and the overall LAW over how professional racing should be handled. Racing interests founded a rival National Cycling Association in 1898. Both organizations had a racing circuit and professional racers had to choose which circuit to join. Major Taylor, chose the LAW circuit despite the fact he was barred, due to his colour, from actual membership, within that organization.

In Canada, Montreal’s case for the world championship was strengthened when a new outdoor wood Velodrome that could hold approx 12,000 spectators was constructed in Verdun by Ucal Henri Dandurand. Interestingly, Dandurand later became the first man in Montreal to own an automobile, something for which he is today best known for.

In contrast, even the location of the Queens Park Velodrome which he built was forgotten and became a subject of debate a few years ago.

In Europe disputes developed between France and Sturmey’s ICA over how many votes should be allocated to the various British Empire countries vs the single vote given to France and its empire.

All these forces came to a head when the 1899 Cycling Worlds Championship were held at Queen’s Park in Verdun. Would France send a team? Which American racers would be permitted to compete, the LAW or the NCA?

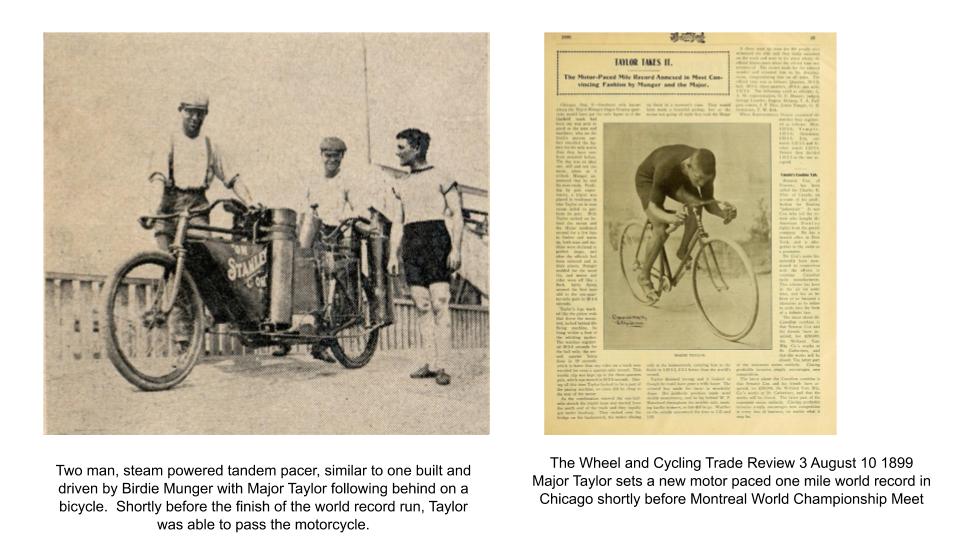

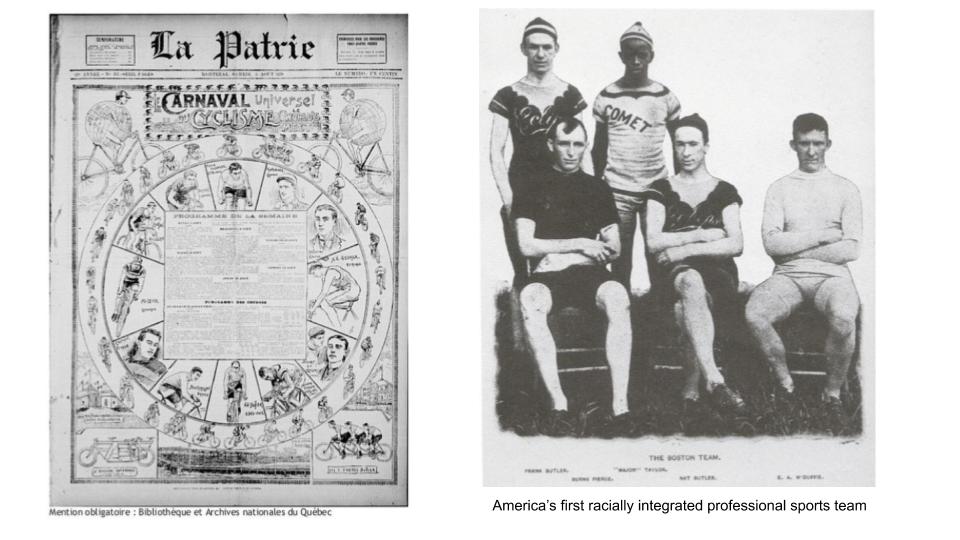

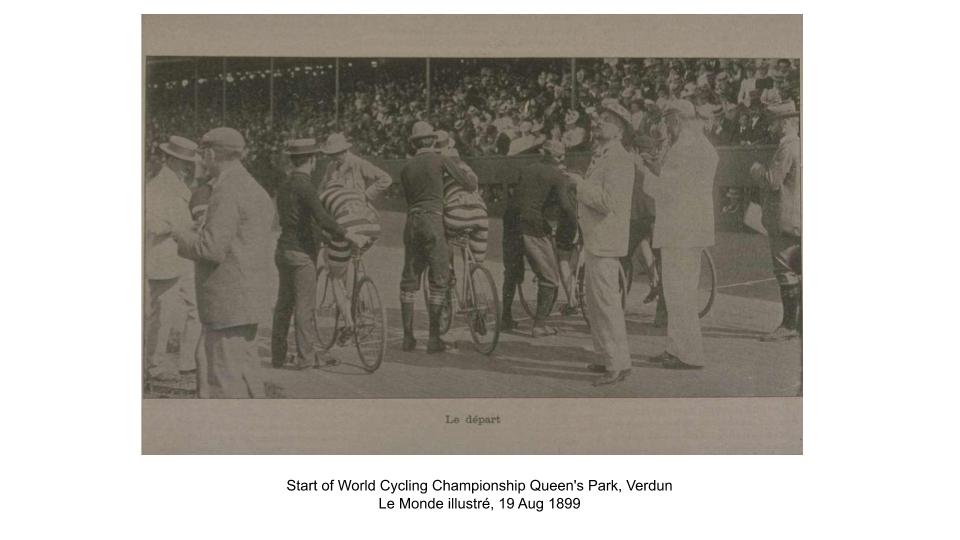

France did send a team and Sturmey, who had travelled to Montreal for the event, held a meeting in the Windsor Hotel, a few days before the championship to choose which American organization he would recognise. He decided in favor of the League of American Wheelmen. This meant that Major Taylor, who had just set a new world motor-paced one-mile speed record was the favorite

along with the Butler brothers of Boston for the highly contested 1 mile professional sprint They had all previously been members of America’s first racially integrated professional sports team. Floyd “The Human Engine” McFarland , Taylor’s pugnacious, bigoted, chief rival was a star rider in the NCA circuit and as such was not permitted to compete in Montreal.

The races at Queens park were held before a capacity audience of 12,000. In the half mile championship race it was widely felt that Major Taylor had won and yet the judges ruled against him. This caused a large uproar in the crowd. However Taylor accepted the judge's decision like a gentleman, earning him much praise. Taylor went on to win the sprint 1 mile professional title becoming only the second black man in history to be a world champion in any sport. (The first was Canadian Black Boxer George Dixon). However, the praise he had earlier received soon turned to scorn from Sturmey. Taylor refused to compete in the traditional match race between the champions of the professional and amateur divisions. He felt that he had much to lose and nothing to gain from competing.

Also, because the NCA racers had not been permitted to compete, his world title was open to dispute.